I. Introduction: Defining Industrial-Grade TIG Welding

1.1 The GTAW Gold Standard: Quality and Precision

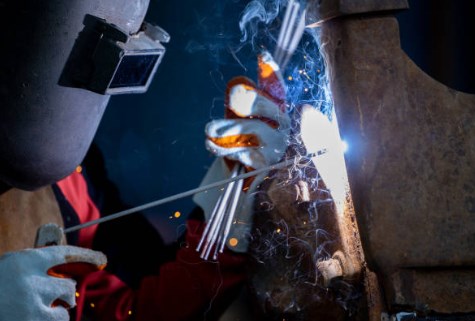

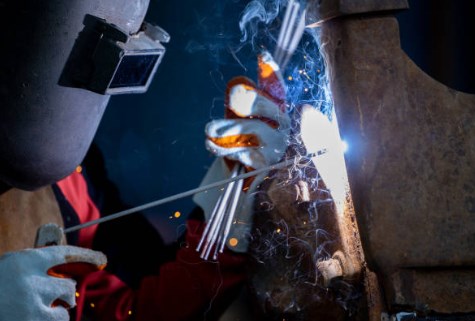

Gas Tungsten Arc Welding (GTAW), universally recognized as TIG welding, holds the unchallenged position as the gold standard for high-quality, high-precision fusion processes. TIG welding is characterized by its use of a non-consumable tungsten electrode to generate the arc and an inert shielding gas (typically argon) to protect the weld puddle and electrode from atmospheric contamination. This method provides superior control over heat input and weld appearance, yielding strong, aesthetically flawless welds with minimal spatter or residue, and virtually eliminating the need for post-weld cleaning.

Because of its meticulous control and ability to handle a wide spectrum of materials—including stainless steel, exotic nickel and titanium alloys, and aluminum—TIG welding is the preferred and often mandatory technique in specialized sectors. These industrial applications include aerospace, nuclear reactor component manufacturing, high-pressure piping, and missile fabrication, where the metallurgical integrity of every joint is considered critically important.

1.2 What Defines Heavy-Duty Industrial Equipment?

Industrial-grade TIG equipment transcends basic fabrication tools by meeting stringent criteria focused on capacity, endurance, and advanced process control. This equipment is categorized by its capability for sustained high-amperage output, typically operating at 200 Amperes (A) and above, and its robust design to maintain peak performance over long production shifts.

Industrial power sources must incorporate advanced digital features, such as highly customizable AC balance and frequency controls, to expertly manage the complexities of specialty metals, particularly when welding aluminum and thick sections. The high cost associated with professional-grade welders, often ranging from $3,000 to $10,000 or more, represents an investment in superior build quality, arc stability, and enhanced durability. For critical fabrication, technological redundancy and process reliability are paramount for managing the financial risk associated with component failure. If a power source provides inconsistent results or overheats, the resulting scrap material and lost production time for highly skilled personnel translate directly into massive financial losses, justifying the premium price for equipment that minimizes this operational risk and ensures regulatory compliance.

II. Industrial Power Sources: Capacity, Control, and Consistency

2.1 Core Power Source Requirements: Constant Current and High-Frequency Arc Ignition

All TIG welding operations necessitate a Constant Current (CC) output power source, which may deliver Alternating Current (AC), Direct Current Electrode Positive (DC+ or DCEP), Direct Current Electrode Negative (DC- or DCEN), or a universal AC/DC capability.

Crucially, industrial TIG welders incorporate an integrated High-Frequency (HF) generator. The HF unit produces high-frequency voltage (several thousand volts) at a minimal current (a fraction of an ampere) to ionize the shielding gas. In DC welding, the HF unit is employed solely for non-contact arc starting, which prevents the tungsten electrode from touching the workpiece and causing contamination. In AC welding, the HF unit operates continuously to stabilize the arc and ionize gases in the arc zone, making the arc easier to maintain as the current rapidly reverses direction.

Machines specifically engineered for TIG welding offer sophisticated internal circuitry, sometimes referred to as "Balanced AC" features. These circuits automatically compensate for the Direct Current Reverse Polarity (DCRP) part of the AC cycle, maintaining the sine waves in equilibrium. This technological advantage is vital for ensuring consistent cleaning, penetration, and weld appearance, especially during AC aluminum welding.

2.2 The Critical Role of Duty Cycle in Production Throughput

For industrial applications, the most important technical specification is the power source's duty cycle. The duty cycle is defined as the percentage of a standard 10-minute period during which the machine can continuously operate at a specified output amperage before its thermal protection system mandates a cooling period.

In high-productivity, continuous manufacturing environments, a high duty cycle is non-negotiable. High amperage settings, required for welding thick materials, drastically reduce the duty cycle due to the intense heat generated by the machine.8 Consequently, industrial fabrication operations frequently demand duty cycles of 80% to 100% at output levels between 250A and 400A to enable continuous, complex, and lengthy weld passes without forced downtime.

Table 1 illustrates the general link between operational amperage, material thickness, and the necessary thermal management system required for continuous industrial output.

Table 1: Industrial Duty Cycle Requirements and Thermal Management

| Continuous Amperage (A) | Typical Material Thickness (Inches) | Minimum Recommended Duty Cycle (at 10 min period) | Cooling Requirement |

| 150 – 200 | 1/8 to 3/16 | 60% – 80% | Air or Water Cooled |

| 200 – 300 | 3/16 to 1/4 | 80% – 100% | Water Cooled (Mandatory) |

| 300 – 500+ | 1/4 and Greater | 100% | High-Capacity Water Cooled |

2.3 Advanced Machine Intelligence: Programmability and Automation

Modern industrial TIG welding is heavily reliant on advanced digital controls. Power sources utilize microprocessor-based control systems that provide superior arc length stability and precise, wide-range arc current measurement. These systems offer backlit graphical displays for easy parameter setup, even in challenging shop lighting conditions.

A significant feature of professional-grade power sources is the inclusion of memory functions and programmability. These machines feature multiple memory locations that allow operators to save and instantly recall specific custom welding procedures. This capability is critical for maximizing consistency and minimizing non-productive setup time when switching between highly varied and complex fabrication tasks—for instance, moving from welding a thin-wall stainless steel pipe to a heavy aluminum plate. The technology built into modern inverter-based power sources dictates operational flexibility and efficiency. Inverter-based machines typically require less heat input (lower amperage) than older transformer models to achieve the same penetration, meaning less heat is generated, which directly extends the machine’s effective duty cycle at a given amperage. Furthermore, this advanced inverter technology is what facilitates the precise control over AC frequency and balance, features that are indispensable for achieving high-quality results on aluminum.

2.4 Mechanized TIG Integration and Automation

Industrial power units are often designed for seamless integration into larger mechanized TIG welding systems. These mechanized setups may incorporate specialized equipment for work handling, automatic filler metal feed mechanisms, devices for checking and adjusting the welding torch level, and automated provisions for initiating the arc and controlling gas and water flow. In specialized applications, such as high-speed tube mills, mechanized TIG equipment can handle extremely high currents, with a 0.250 inch diameter tungsten electrode capable of using up to 600 amperes.

III. Managing Heat: Torches, Coolers, and Remote Controls

3.1 The Absolute Need for Water-Cooled Torches

For industrial TIG welding, thermal management is a fundamental constraint on productivity. When continuous operation exceeds 200 amperes, relying on an air-cooled torch is highly impractical due to the thermal load, making a water-cooled system an absolute necessity.

Water-cooled torches mitigate high thermal loads by circulating coolant directly through the electrode lead, which also carries the welding current. A water-cooled TIG machine setup requires three distinct lines running to the torch: one plastic hose for the inert shielding gas (preventing contamination), a woven metal tube combining the current lead and coolant feed, and a third hose for the return coolant, directed back to the storage reservoir or a drain.

3.2 Water Cooler System Requirements and Flow Physics

The integrity of the industrial welding system hinges on the efficiency of the cooling loop. The water cooler system must be configured precisely to protect the torch components. The maximum recommended output pressure for TIG torches is 50 psi. Most standard TIG torches require a desired flow rate of 1 quart of water flow per minute (approximately 0.95 L/min).

System operators must understand the physics of cooling: increasing the flow rate beyond the recommended minimum, such as 1 quart per minute for standard torches, will not provide measurable additional cooling and may actually reduce the efficiency of the water cooler by moving the heated water through the radiator system too quickly. To ensure thermal protection is always active, coolers should be connected to the power supply’s auxiliary outlet; this guarantees the cooler is running whenever the welder is powered on, protecting the torch from accidental burnout. In heavy-duty fabrication, operational failure often stems not from the arc itself, but from the cooling loop. A subtle drop in water pressure—perhaps due to a pump failure or a clogged coolant line—immediately compromises the torch's thermal efficiency, forcing operators to lower the amperage or risk component damage. Continuous monitoring of water pressure and flow rate is therefore a critical element of industrial maintenance protocol.

3.3 High-Amperage Torch Components

In high-amperage applications, specialized torch components are mandatory for thermal endurance. Standard ceramic nozzles are generally rated for use up to 275 amperes; however, heavy-duty industrial jobs exceeding 300 amperes require specialized metal-coated or solid metal nozzles.

Electrode holders (torches) themselves are defined by a duty-cycle rating, which specifies the maximum current the holder can safely withstand in a 10-minute interval. Industrial torches are constructed to allow for the ready exchange of electrodes and gas nozzles.

3.4 Maximizing Control: Remote Amperage Controls

The ability to dynamically adjust heat input is essential in industrial TIG welding, where joint geometry or material thickness can change mid-pass. Remote amperage controls provide this flexibility.

The most common control is the Foot Rheostat (or foot pedal), which allows the operator continuous, hands-free control over the welding current, facilitating precise current ramping up and down throughout the weld. For welding large, fixed components or performing complex positional welds (such as vertical or overhead positions ) where a foot pedal is impractical, Fingertip and Hand Controls are necessary. These devices, which include rotary dials, linear controls, or momentary switches, allow the welder to adjust the current on the fly, providing crucial flexibility for maintaining bead quality in challenging positions.

IV. Consumables: Specialized Tungsten and Gas Management

4.1 Selecting the Right Tungsten Electrode for Industrial Work

Tungsten, with the highest melting point of any pure metal at 3,422 °C (6,192 °F) , forms the basis of the GTAW process. Industrial applications rely on specialized electrode compositions to optimize current capacity and arc stability.

For DC Welding (used predominantly for stainless steel, carbon steel, titanium, and exotic alloys), rare-earth electrodes are preferred. Specifically, 1.5% Lanthanated (Gold) or 2% Lanthanated (Blue) electrodes are popular choices because they provide easier arc striking, maintain their sharp tip geometry longer, and offer superior current-carrying capacity compared to pure tungsten.

For AC Welding (essential for aluminum and magnesium), Zirconiated (0.8% white) or Pure Tungsten (Green) electrodes are employed. Zirconiated is highly valued for its stable arc and resistance to contamination, allowing it to handle higher amperage levels effectively during AC operation.

4.2 Tungsten Tip Geometry and Arc Performance

The geometry of the tungsten tip provides direct control over arc focus, penetration depth, and resulting bead width.

Standard Industrial Use: Most general-purpose fabrication utilizes a truncated tip ground to an included angle between 30 and 60 degrees. This range provides the most balanced performance, achieving adequate penetration depth and excellent arc stability.

Deep Penetration: Angles exceeding 60 degrees are used to maximize penetration and produce a narrower bead profile, though the arc may tend to wander.

Low Amperage/Thin Stock: Very sharp angles, around 15 degrees, are typically reserved for low-amperage applications or outside corner joints, as they widen the arc coverage and intentionally reduce deep penetration.

4.3 High-Capacity Tungsten Amperage Ratings

To utilize the high output of industrial power sources fully, the tungsten electrode diameter must be correctly matched to the required current. For manual welding and smaller mechanized processes, this sizing is crucial for preventing the electrode from melting or fragmenting, which would cause weld contamination. For instance, a 1/8 inch (3.2 mm) Lanthanated electrode can sustain currents up to 350 A under DCEN conditions.

Table 2 provides general amperage guidelines for DCEN operation with common electrode sizes and compositions suitable for industrial environments.

Table 2: General Amperage Capacity Guide for DCEN TIG Welding (Argon Shielding)

| Electrode Diameter (Inches) | Standard Range (A) | 1.5% Lanthanated (Gold/Blue) Amps | 2% Ceriated (Grey) Amps |

| 0.040" (1.0mm) | 15 – 80 A | 15 – 80 A | 15 – 70 A |

| 1/16" (1.6mm) | 70 – 150 A | 80 – 150 A | 70 – 130 A |

| 3/32" (2.4mm) | 140 – 235 A | 150 – 250 A | 150 – 220 A |

| 1/8" (3.2mm) | 220 – 325 A | 240 – 350 A | 220 – 330 A |

| 5/32" (4.0mm) | 300 – 425 A | 400 – 500 A | 375 – 475 A |

4.4 Precision Shielding Gas Systems and Flow Control

Shielding gas selection is critical for achieving required penetration and travel speeds. While 100% Argon is standard for TIG, industrial welding of thicker metals or specialty alloys often mandates the use of Argon/Helium mixtures or pure Helium. Helium, being lighter and requiring a higher arc voltage, generates a significantly hotter arc, leading to increased penetration and faster travel speeds.

Welders typically prefer rotameter-style flowmeters over standard pressure regulators for shielding gas control. Flowmeters measure the actual volume of gas delivered (typically in Cubic Feet per Hour, CFH), providing visual confirmation via a floating ball that the precise, critical flow rate is maintained. This accuracy is vital for reducing the risk of contamination from insufficient flow and minimizing wasted gas.

4.5 Gas Lens Technology: Laminar Flow and Visibility

For critical and out-of-position welds, a gas lens is indispensable. A gas lens replaces the standard collet body and utilizes internal mesh screens or a porous filter to smooth the turbulent gas flow into a predictable, laminar (streamlined) stream.

This laminar flow provides superior, wider, and more uniform shielding coverage without increasing gas consumption. Furthermore, the use of a gas lens allows the operator to extend the tungsten electrode significantly farther past the nozzle—sometimes up to 1 inch. This increased tungsten stickout dramatically improves visibility and accessibility for welding complex geometries or reaching deep joint roots (such as TKY joints in structural piping).

4.6 Optimizing Pre-Flow and Post-Flow for Protection

Shielding gas management extends beyond the moment the arc is active. Post-flow—the continuation of gas flow after the arc extinguishes—is essential to protect the solidifying weld pool and the cooling, hot tungsten electrode from atmospheric oxidation.

A dependable standard for determining post-flow time is to set the duration in seconds by dividing the peak welding amperage by 10. For example, a 200 A weld requires a minimum post-flow of 20 seconds. A minimum of 8 seconds is recommended regardless of amperage.

The selection of tungsten diameter and the amperage setting fundamentally limit the utilization of industrial power sources. High current requires larger diameter tungsten. When operating at high currents (over 200 A), intense upward convection currents generated by the heat necessitate a corresponding increase in the Argon flow rate by 15% to 25% to effectively compensate for turbulence. If the flow rate is not increased proportionally, the highly focused heat will draw in ambient air, leading to porosity or oxidation, especially when welding sensitive materials like stainless steel or titanium. Therefore, maximizing machine capacity requires synchronous, interdependent adjustments to flow rate, post-flow time, and tungsten sizing/geometry.

V. Advanced Process Control: Mastering Specialty Alloys

Industrial fabrication often involves advanced welding techniques to manage complex thermal dynamics, particularly when working with heat-sensitive or thick materials.

5.1 TIG Pulsing (GTAW-P): Thermal Cycle Control

Pulsed TIG welding involves the rapid cycling of current between a high peak amperage (to drive penetration) and a low background amperage (to allow the weld pool to cool slightly). This precise thermal control minimizes heat distortion on thin, sensitive materials while achieving deep penetration.

High-Speed Pulsing: Utilizing high pulse frequencies (e.g., 100 Hz or more) constricts and focuses the arc, enhancing penetration and increasing potential travel speed. This is highly effective in automated systems for welding thick sections where a narrow, focused weld profile is necessary.

Low-Frequency Pulsing: Very low pulse frequencies (around 1 to 2 Hz) function primarily as a manual aid. The rhythmic brightening and dimming of the arc provide the welder with a visual metronome to time the controlled addition of filler metal.36 This technique is leveraged to produce the highly sought-after "stacked dime" aesthetic and offers greater control for out-of-position welds or welding near edges.

5.2 AC TIG Mastery for Aluminum and Magnesium

Alternating Current (AC) TIG welding is required for aluminum and magnesium alloys because the polarity reversal cycle breaks down the refractory, high-melting-point aluminum oxide layer that forms naturally on the surface of the base metal.

AC Balance Control (EN vs. EP): The AC balance control allows the operator to adjust the ratio of Electrode Negative (EN, which focuses heat into the workpiece for penetration) versus Electrode Positive (EP, which cleans the oxide layer but directs more heat toward the tungsten). For clean aluminum, a starting point is often around 75% EN. However, dirtier or heavily oxidized aluminum may require the balance to be lowered (more EP, perhaps down to 65%) to increase the cleaning action. Operators must be aware that favoring EP significantly increases the thermal load on the tungsten tip.

AC Frequency Control (Hz): This control manages the lateral stiffness and concentration of the arc cone. High frequency (e.g., 150 to 250 Hz) focuses the arc, which is beneficial for controlling the weld pool on thin materials and preventing excessive heat buildup over a large area. Conversely, a low frequency (e.g., 80 to 120 Hz) produces a wider arc cone, which is often better suited for spreading heat input across thick materials (3/8 inch and above) to achieve optimal wetting and fusion.

The precise control afforded by advanced waveform features (AC Balance and AC Frequency) fundamentally changes the effective amperage utilized by the material. For aluminum, the conventional rule of thumb (1 ampere per 0.001 inch of thickness) often deviates because waveform settings optimize energy transfer. A tightly focused, high-frequency arc requires a higher peak amperage to penetrate than a wider, low-frequency arc. Similarly, optimizing the EN setting transfers energy into the work piece more efficiently, effectively enabling the welder to achieve desired results with lower overall power source output. This digital optimization extends the operational window of the equipment.

5.3 DC TIG for Stainless Steel and Exotic Alloys

Direct Current Electrode Negative (DCEN) configuration provides maximum penetration and minimal thermal wear on the tungsten, making it the default choice for welding stainless steel, carbon steel, and titanium.

Stainless steel, in particular, demands meticulous shielding protocols due to its sensitivity to oxidation at high temperatures. Post-flow gas coverage is critically important to prevent the formation of highly undesirable chromium oxides, often referred to as "sugaring," which compromise corrosion resistance. For open-root pipe welding and pressure vessel fabrication, dedicated root protection (purging) using a separate inert gas supply is mandatory to prevent oxidation on the back side of the root pass.

Table 3 provides a set of validated starting parameters for industrial AC TIG welding of aluminum, demonstrating the interrelation of parameters for specific thicknesses.

Table 3: Example Starting Parameters for AC TIG Welding Aluminum (Industrial Grade)

| Material Thickness (Inches) | Amperage Range (AC Peak) | Tungsten Diameter | Shielding Gas | AC Frequency (Hz) | AC Balance (% EN) |

| 1/8 (3.2 mm) | 125 – 150 A | 3/32" (2.4mm) | 100% Argon | 180 – 250 | 70 – 75% |

| 3/16 (4.8 mm) | 180 – 215 A | 1/8" (3.2mm) | 100% Argon or Ar/He Mix | 120 – 180 | 75 – 80% |

| 1/4 (6.4 mm) | 260 – 300 A | 5/32" (4.0mm) | Argon/Helium Mix | 80 – 120 | 75 – 80% |

VI. Operational Integrity: Maintenance and Troubleshooting

6.1 Preparation is Non-Negotiable: The Foundation of TIG Quality

Proper industrial preparation requires more than just a quick wipe. It involves mechanical removal of heavy contamination (grinding or wire brushing) followed by a solvent wipe, particularly for metals like aluminum, which have a naturally occurring oxide layer that is highly porous and easily traps contaminants.

6.2 Identifying and Correcting Common Industrial Defects

Industrial operations rely on rapid troubleshooting to maintain efficiency. Several common defects arise from incorrect equipment setup or inadequate procedure controls:

Porosity: This defect is characterized by gas pockets trapped in the weld metal. It is typically caused by inadequate shielding gas coverage due to insufficient flow rate, insufficient post-flow time, or welding in a strong draft. Correction: Use a flowmeter (rotameter) to confirm the exact gas volume delivery , increase post-flow time (Amps/10) , and, if possible, switch to a gas lens setup to ensure a more stable, laminar shield.

Weld Graininess or Lack of Fusion: A grainy appearance or poor tie-in at the root often indicates insufficient heat input relative to the travel speed or an incorrect filler metal choice. Correction: Increase the base amperage setting, or utilize the remote control to ensure consistent heat application, and verify the correct filler metal alloy is used for the base material.

Sugaring/Oxidation on Stainless Steel: A gray, dull, or blackened appearance on stainless steel indicates the material was exposed to the atmosphere while still glowing hot, forming chromium oxides. Correction: The critical solution is extending the post-flow time and ensuring that root purging is meticulously maintained for pipe and open-root joints.

Tungsten Inclusion: Direct contamination of the weld pool caused by the tungsten electrode touching the molten metal. Correction: This usually signifies a tungsten electrode that is improperly sized or shaped for the amperage used , incorrect arc length control , or failure of the High-Frequency start system, forcing the welder to scratch-start.

VII. FAQs of High-Amperage TIG Welding Equipment

Q1: Why do industrial processes require an increase in Argon flow when welding above 200 amps?

A: Welding at high currents generates intense heat, which creates strong upward convection currents around the arc. These currents can pull ambient, contaminating air into the shielding gas zone. To effectively counteract this turbulence and ensure the molten weld pool remains fully protected, the argon flow rate must be increased, typically by 15 to 25% above standard recommendations.

Q2: Is it beneficial to use a wireless remote control system in a fabrication facility?

A: Yes. In large industrial environments, particularly those involving large fixed structures, running long cables poses safety risks (tripping hazards) and operational impediments. Wireless remote controls provide the operator with the same dynamic control over amperage (via fingertip or foot pedal styles) as traditional corded units, but without the physical limitations, thus enhancing safety and mobility.

Q3: What is the benefit of a flowmeter over a pressure regulator for shielding gas?

A: A flowmeter, utilizing a rotameter design, measures the actual volumetric flow rate (CFH or L/min) of the shielding gas delivered to the torch, rather than just the pressure. This visual confirmation provides the highest level of assurance that the critical flow volume is accurately maintained, minimizing the risk of contamination caused by insufficient flow and leading to more efficient gas usage.

Q4: How does the thickness of the material influence industrial TIG parameters?

A: Welding thicker materials necessitates substantially higher amperage to achieve adequate penetration. This, in turn, requires larger diameter tungsten electrodes and often mandates the use of hot-running shielding gases, such as Argon/Helium mixtures. Furthermore, thicker metals often benefit from lower AC frequency settings (around 80 to 120 Hz) to achieve a wider, more manageable weld bead profile. The increased thermal mass also requires significantly longer post-flow times.

Q5: When should the machine's program memory functions be utilized?

A: Memory functions are critical for guaranteeing consistency and repeatability in high-value production environments. They should be utilized whenever an operator needs to switch between distinct, verified welding procedures—such as changing from pulse welding thin titanium to standard AC welding thick aluminum. Saving specific parameters like AC Balance, Pulse frequency, pre/post-flow times, and amperage ramps ensures that the exact, compliant procedure can be instantly recalled, minimizing setup errors and variations between different operators.

Conclusion

Heavy-duty industrial TIG welding is a technical discipline requiring a systemic approach where power generation, thermal stability, and precise digital control converge. Success in critical fabrication is dependent on investing in power sources capable of sustained high-amperage output with superior duty cycles (80% to 100%). These machines must be supported by mandatory water-cooling loops, maintained with strict pressure and flow rate control, and operated using advanced remote controls for dynamic heat input management.

Mastery of industrial TIG further relies on specialized consumables: utilizing rare-earth tungsten electrodes sized appropriately for the current load and employing laminar flow systems (gas lenses) for reliable atmospheric protection. The application of advanced digital features—specifically AC balance, AC frequency, and pulsing controls—allows operators to metallurgically engineer the weld profile, ensuring high-quality, inspection-ready results on high-value and exotic materials. Ultimately, the robust specification and meticulous maintenance of all components, from the power source to the tungsten tip, are prerequisites for achieving both production efficiency and uncompromising metallurgical integrity in heavy industry.

Related articles:

1. Chinese Welding Equipment Industry were Invited to the Global Manufacturing Base

2. How to Choose the Best Automotive Welding Equipment?

3. Arc Welding Tools and Equipment List

4. A Guide to Heavy Industrial TIG Welding Tools & Equipment

5. Container Welding Guide: Techniques, Equipment, Quality Control