The technical landscape of Gas Metal Arc Welding (GMAW), commonly known as Metal Inert Gas (MIG) welding, is defined by the precise manipulation of variables to achieve metallurgical fusion. Among the most fundamental yet hotly debated operational decisions is the travel direction of the welding torch. The choice between the push and pull techniques—often referred to as forehand and backhand welding—is not merely a matter of ergonomic comfort but a decision that dictates the fundamental physics of the arc, the thermal distribution within the substrate, and the structural integrity of the resulting joint. While a casual observer might see only a torch moving across a plate, the professional welder understands that the angle and direction of that torch govern the depth of penetration, the morphological profile of the bead, and the effectiveness of the shielding gas envelope.

I. The Fundamental Mechanics of Travel Direction

At the core of the MIG welding process is the establishment of an electric arc between a continuously fed solid wire electrode and the base metal workpiece. This arc serves as a high-intensity heat source that simultaneously melts the filler wire and a localized portion of the base metal to form a molten weld pool. The direction in which the welder moves this pool relative to the torch nozzle defines the technique.

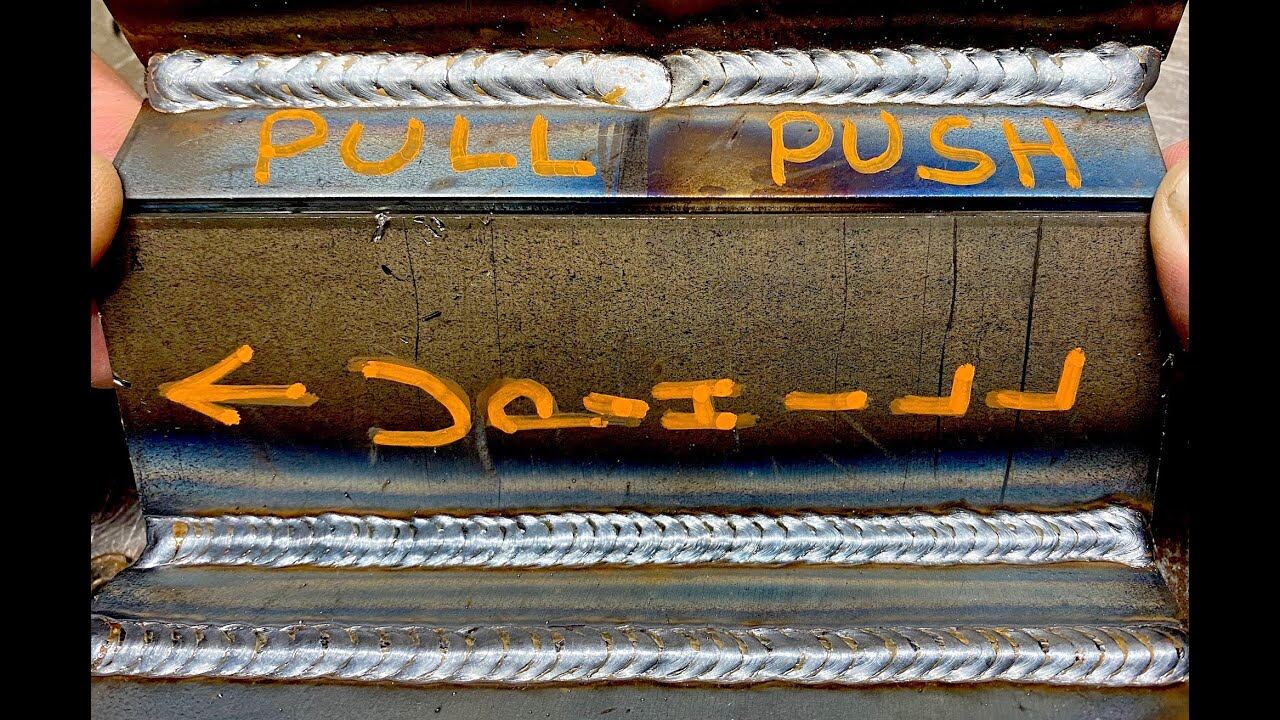

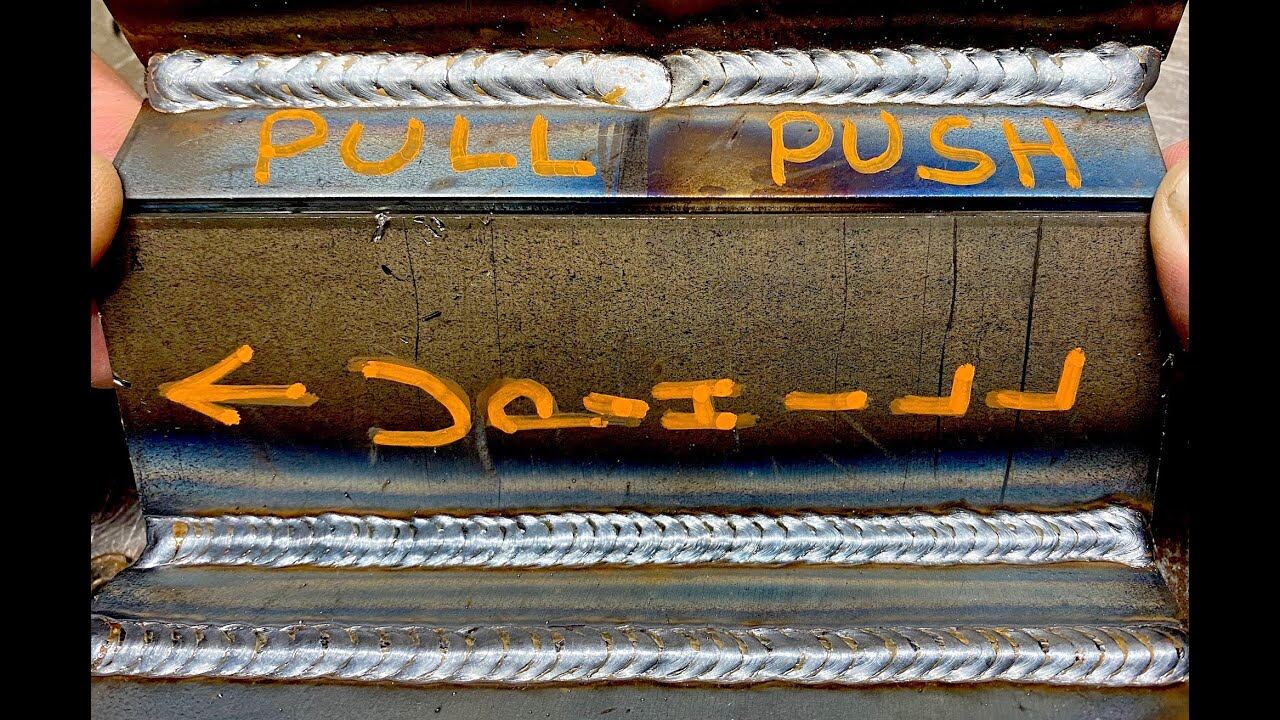

The push technique, or forehand welding, involves positioning the torch such that it points away from the completed weld bead, moving in the direction of the unwelded joint. In this orientation, the torch is typically tilted at a travel angle of 5 to 15 degrees toward the direction of travel. This leads the arc to act upon the cold base metal ahead of the pool, while the arc force itself "pushes" the molten metal and shielding gas forward.

Conversely, the pull technique, also known as the drag or backhand technique, involves tilting the torch away from the direction of travel, effectively "dragging" the weld pool behind the arc. Like the push method, it utilizes a 5 to 15-degree inclination, but the nozzle points back toward the deposited metal. The arc force in this configuration is directed back into the molten pool, which significantly alters the thermal dynamics of the fusion zone.

II. Thermodynamic Interactions and Heat Input

The primary differentiator between these techniques lies in how heat energy is transferred to the workpiece. The physics of the arc involve a plasma stream that exerts mechanical pressure on the molten metal. The direction of this pressure determines how much of the arc's energy is used to melt the base metal (penetration) versus how much is used to spread the filler metal across the surface (bead width).

Heat input is a critical metric for maintaining the mechanical properties of the parent material and is calculated by the relationship between voltage, amperage, and travel speed. The standard formula for heat input (H) in a non-waveform controlled process is expressed as:

in a non-waveform controlled process.png)

In this equation, V represents arc voltage, A represents amperage, and S is the travel speed in millimeters per minute. Furthermore, the thermal efficiency (u) of the process must be considered to determine the actual energy delivered to the weld area (Q):

.png)

For MIG/MAG welding, the thermal efficiency factor (n) is typically estimated at 0.8. The travel direction influences the travel speed (v), which in turn modulates the cooling rate (t{8/5}) of the weld and the surrounding Heat-Affected Zone (HAZ).

In a push technique, the arc force is dispersed across the leading edge of the puddle. This causes the molten metal to flow forward, creating a "cushion" that absorbs some of the arc's energy. This dispersion results in a shallower temperature gradient and a broader distribution of heat, which is advantageous for preventing burn-through on thin-gauge materials.

In the pull technique, the arc is directed toward the root of the joint without the cushioning effect of the leading puddle. This concentration of energy allows the arc to "dig" deeper into the base material, facilitating superior fusion at the root. However, this concentrated heat also increases the risk of excessive grain growth in the HAZ, which can negatively impact the ductility and toughness of the joint if not properly managed.

III. Comparative Dynamics of Pushing and Pulling

| Feature | Push Welding (Forehand) | Pull Welding (Backhand/Drag) |

| Arc Direction | Pointed ahead toward cold metal | Pointed back toward deposited metal |

| Puddle Interaction | Arc is cushioned by the leading edge | Arc acts directly on the root/thin pool |

| Heat Distribution | Dispersed and broad | Focused and concentrated |

| Travel Speed Capability | Generally faster | Generally slower and more controlled |

| Penetration Depth | Shallow to moderate | Deep and aggressive |

| Bead Morphology | Flat and wide | Convex (tall) and narrow |

IV. Bead Morphology and Aesthetic Considerations

The aesthetic requirements of a weld vary significantly between heavy industrial fabrication and consumer-facing applications like automotive restoration or artistic metalwork. The travel technique is the primary tool a welder uses to control the "wetting" of the bead—the way the molten metal flows and adheres to the edges (toes) of the joint.

Push welding is widely preferred for any application where a smooth, professional-looking finish is required. Because the arc force pushes the puddle forward, the molten metal naturally washes out toward the toes of the weld, creating a flatter profile with a more gradual transition to the base metal. This reduced "reinforcement" (the height of the weld bead) minimizes the need for post-weld grinding and polishing, which can be a significant labor cost in manufacturing.

Pull welding, by contrast, results in a narrower and taller bead profile. As the arc focuses heat in the center of the joint, the filler metal tends to stack up rather than spread out. While this produces a highly visible "ropey" appearance that may require more cleanup if aesthetics are a priority, it provides extra metal in the center of the joint, which can be beneficial in certain structural repairs where reinforcement is desired over flush finishes.

V. Shielding Gas Dynamics and Atmospheric Protection

A primary function of the MIG gun is the delivery of an inert shielding gas, typically Argon or a mixture of Argon and Carbon Dioxide (CO2), to protect the molten pool from oxygen and nitrogen. Contamination by atmospheric gases leads to oxidation and porosity—the formation of small bubbles or voids in the solidified weld metal that drastically reduce strength.

The push technique is inherently superior for gas coverage in flat and horizontal positions. Because the nozzle is tilted forward, the shielding gas is projected ahead of the arc, effectively "pre-purging" the joint of air before the metal is melted. This ensures that the hottest part of the fusion zone is always encased in a protective atmosphere.

In the pull technique, the shielding gas is directed back over the already solidified or cooling weld bead. While this provides excellent post-weld cooling protection, the leading edge of the arc is closer to the edge of the gas envelope. In windy or drafty environments, the pull technique is more susceptible to gas turbulence, which can suck air into the weld zone and cause surface porosity.

VI. Material-Specific Application Standards

Professional welding standards are often dictated by the metallurgical characteristics of the base metal. The choice between push and pull is rarely optional when dealing with non-ferrous metals like aluminum or when utilizing specialized consumables like flux-cored wire.

1) The Critical Role of Push Welding in Aluminum:

Aluminum welding presents unique challenges due to the metal's high thermal conductivity and the presence of a tenacious refractory oxide layer on its surface. For aluminum, the push technique is not just a preference; it is a technical requirement.

The arc in a MIG process has a "cleaning action" that breaks up the aluminum oxide layer. When pushing, the arc and gas hit the cold metal first, cleaning the path for the molten puddle to follow. Furthermore, because aluminum dissipates heat so rapidly, the broad, dispersed heat of the push technique helps maintain a stable pool without the localized intensity that would cause the metal to collapse or burn through. Dragging on aluminum often leads to "sooty" welds characterized by black oxide entrapment and severe porosity.

2) Structural Steel and the Advantages of Pulling:

In structural steel fabrication, where the goal is often maximum strength on thick plates (exceeding 1/4 inch or 6mm), the pull technique is the industry standard. The aggressive "dig" of the backhand technique ensures that the filler metal is deeply fused into the root of the joint. For multi-pass welds on heavy equipment or structural frames, the first pass (root pass) is almost always dragged to ensure absolute fusion, while subsequent "fill" and "cap" passes may be pushed to create a smoother finish that blends into the surrounding metal.

3) Slag Management in Flux-Cored Arc Welding (FCAW):

The introduction of flux-cored wire changes the physics of the pool by introducing liquid slag. The professional mandate for any slag-producing process is "If there's slag, you must drag".

If a welder attempts to push a flux-cored weld, the forward motion of the torch pushes the molten slag ahead of the arc. The arc then travels over this slag, trapping it beneath the weld metal and causing a "slag inclusion"—a serious defect that can cause the weld to fail under stress. Pulling (dragging) ensures that the slag stays behind the arc, allowing it to float to the surface of the puddle and solidify as a protective layer that can be easily chipped off after cooling.

4) Technique Guide by Material and Consumable

| Material/Wire Type | Primary Technique | Technical Justification |

| Aluminum Alloys | Push (Always) | Oxide cleaning and thermal management |

| Thin Mild Steel (<1/8") | Push | Prevents burn-through; wider coverage |

| Heavy Steel Plate (>1/4") | Pull (Drag) | Ensures deep root penetration and strength |

| Stainless Steel | Push (Aesthetic) | Better gas coverage for corrosion resistance |

| Gasless Flux-Core (FCAW) | Pull (Drag) | Essential to prevent slag inclusions |

| Solid Wire with CO2 | Pull (Drag) | Stabilizes high-spatter arc in pure CO2 |

VII. Positional Welding and the Battle Against Gravity

The difficulty of MIG welding increases significantly when moving out of the flat position (1G/1F). In vertical (3G/3F) and overhead (4G/4F) positions, gravity acts as a constant force that threatens to pull the molten metal out of the joint.

1) Vertical Welding: Uphill vs. Downhill:

Vertical welding is categorized by direction rather than just push or pull. Vertical uphill welding is generally the structural standard for thick materials. It utilizes a "pushing" motion directed upward, allowing the welder to build a "shelf" of solidified metal that supports the molten pool above it. This technique facilitates deep penetration and allows for better heat management, reducing the risk of the metal overheating and sagging.

Vertical downhill welding is a high-speed technique used primarily for thin sheet metal. It is more akin to a dragging motion where the welder stays ahead of the puddle to avoid "cold lap"—a condition where the molten metal flows ahead of the arc and acts as an insulator, preventing the arc from fusing to the base metal. Downhill welding provides very shallow penetration, which is ideal for preventing burn-through on automotive panels.

2) Overhead Challenges:

In the overhead position, both push and pull techniques are used, but the pull technique is often favored by experienced operators for its directional stability. Dragging the torch allows for a more controlled deposition rate, and the arc force helps keep the molten metal pushed up into the joint. Regardless of the direction, travel speeds in the overhead position must be fast, and amperage must often be lowered to prevent the pool from becoming too large and falling out due to gravity.

VIII. Operational Efficiency: Visibility and Ergonomics

A welder’s ability to see the joint and maintain a steady hand directly correlates to weld quality. The choice of travel direction fundamentally changes the operator’s field of view and physical stability.

Visibility is often cited as the primary reason many welders prefer the push technique. Because the nozzle is tilted forward, the operator has a clear line of sight to the unwelded joint ahead. This is essential for following precise lines or complex joint geometries. However, the push technique forces the welder to look over the "shoulder" of the nozzle, which can sometimes obstruct the view of the actual arc-puddle interface.

Pull welding offers a different visual advantage: a perfect view of the "puddle apex" and the deposition rate. By dragging the torch, the welder can see exactly how the filler metal is stacking up and adjust travel speed in real-time to ensure uniform bead height.

Ergonomically, pull welding is often considered superior for long joints. Because the welder is moving away from the starting point toward cold, unwelded metal, they can rest their hand or arm on the workpiece for stability. In push welding, the welder is moving toward or over the hot bead, which can make it difficult to find a stable resting point without risking thermal discomfort or damage to protective gear.

IX. Troubleshooting Techniques and Common Defects

Even with the correct direction of travel, improper execution can lead to a variety of weld defects. Professional welders use travel direction as a primary variable to troubleshoot and correct bead irregularities.

1) Managing Spatter and Bead Profiles:

Excessive spatter is often a result of incorrect electrical settings, but travel direction plays a secondary role. Pull welding generally results in a more stable arc and slightly less spatter because the arc is directed back into the molten pool, which dampens the explosive forces of droplet transfer. If a push technique is resulting in excessive "BBs" (small balls of spatter), a welder might switch to a slight drag or check for inadequate gas coverage, as turbulent gas flow can also cause an erratic arc.

"Ropey" or excessively convex beads are a sign of a "cold" weld—where there is insufficient heat to allow the metal to wash out. While this is common in pull welding, if it becomes excessive, the welder should increase voltage or consider switching to a push technique to flatten the profile. Conversely, if the bead is too thin or showing "undercut" (a groove melted into the base metal at the toe), the welder should slow down or switch to a pull technique to increase reinforcement.

2) Troubleshooting Summary Table:

| Problem | Potential Cause (Technique Related) | Recommended Technical Adjustment |

| Burn-Through | Travel speed too slow; Pulling on thin metal | Switch to Push; Increase travel speed |

| Lack of Fusion | Travel speed too fast; Pushing on thick metal | Switch to Pull; Slow travel speed; Increase Amps |

| Surface Porosity | Turbulent gas flow; Pulling in drafts | Use Push for better coverage; Reduce torch angle |

| Slag Inclusions | Pushing flux-cored wire | Switch to Pull (Always drag slag) |

| Inconsistent Width | Poor visibility of joint | Switch to Push to see path; Use steady hand rest |

Conclusion

The "Push vs. Pull" debate is not about identifying a single superior method, but about selecting the right tool for the metallurgical and structural requirements of the project. A professional welder must be proficient in both.

The push technique is the primary choice for modern manufacturing, automotive fabrication, and aluminum work. It offers the best balance of speed, aesthetic finish, and gas coverage. However, the pull technique remains the cornerstone of heavy structural welding and is the only safe method for flux-cored processes.

To maximize the quality of a MIG weld, operators should adhere to the following best practices:

Always push aluminum to ensure oxide cleaning and superior gas coverage.

Always pull flux-cored or slag-producing wires to prevent internal defects.

Use a push technique for aesthetic, visible welds to reduce post-weld labor.

Maintain a travel angle of 5 to 15 degrees; steeper angles jeopardize gas coverage and arc stability.

Leverage advanced inverter technology, such as that provided by Megmeet, to stabilize the arc and minimize spatter across all welding positions and directions.

By understanding the underlying physics of these techniques, welders can move beyond personal preference to achieve the precision and structural integrity demanded by professional industrial standards.

FAQs

Q1. Which technique is better for a beginner learning MIG welding?

Most instructors recommend starting with the push technique. It encourages the habit of "watching the puddle" and focusing on the leading edge of the arc, which is essential for consistent bead formation. Since much modern MIG work is on thin-to-medium materials, pushing is the more versatile starting point.

Q2. Does pushing or pulling create a stronger weld?

On standard thickness steel, the strength is essentially the same. However, the pull technique provides deeper penetration, which is vital for the structural integrity of heavy plates. A push weld that doesn't penetrate to the root of a thick joint is technically "weaker" due to the lack of fusion at the bottom.

Q3. Why does my weld look black and sooty when I drag on aluminum?

Dragging on aluminum directs the shielding gas back over the cooling weld but leaves the front of the arc exposed. Aluminum oxidizes instantly; without the "pre-purging" and cleaning action of the push technique, the arc hits the oxide layer and creates soot, resulting in a weak, contaminated weld.

Q4. Can I use a push technique for vertical up welding?

Related articles:

1. Exhaust Pipes MIG Welding Guide: Tips, Settings, and Practices

2. Mastering MIG Welding Tips for High Carbon Steel Welding

3. MIG Welding Aluminum Essential Tips and Techniques

4. MIG Welding on Stainless Steel: Tips, Techniques, Applications

5. Industrial MIG Welding: Setting the Correct Parameters

in a non-waveform controlled process.png)

.png)